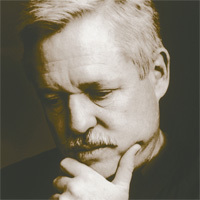

Armistead Maupin has delighted millions, straight and gay, with his stories of swinging San Francisco.

Armistead Maupin has delighted millions, straight and gay, with his stories of swinging San Francisco.

Though Maupin was one of the first of a new breed of openly gay authors, his appeal has always resided in his inclusiveness as a storyteller.

For over thirty years his beloved characters from 28 Barbary Lane in the ‘Tales of the City’ series have cut an unprecedented path through popular culture, from a groundbreaking newspaper serial to six internationally bestselling novels published in eleven languages, to a Peabody Award-winning miniseries.

Maupin’s latest work ‘Michael Tolliver Lives’ is a novel about the act of growing older joyfully and the everyday miracles that somehow make that possible. This month is a rare opportunity to hear this witty and engaging author in Perth.

- When: Wed 7.30-9pm Sep 26

- Where: Octagon Theatre, UWA

- Tickets: Standard $39. If you book four people on the course you get a fifth place free. Just select the 5 for 4 Offer option when enrolling. Please advise us of all names of the members of your group by fax 6488 1066 or email extension@uwa.edu.au.

- Bookings: 08 6488 2433 or www.extension.uwa.edu.au

Zoe Carter spoke to Armistead Mauphin about his latest novel, Michael Tolliver Lives, finding love and the perfidy of Australians.

Zoe Carter: You’ve said in the past that your characters express certain parts of yourself. Do you find characters are a way to learn more about yourself?

Armistead Maupin: When Maryanne turned too ambitious for anyone’s good in the last ‘Tales of the City’ book, that was something of a warning to myself to not let ambition get in the way of love and connection. But yeah I’ve only had one character channel through this time and I would say I was examining I think more of the romantic (hmmm) side of myself probably but other characters represent different things to me.

Z: Why did you chose to pick up a character from Tales and write from a first person perspective this time?

A: It was about offering a more intimate glimpse at Michael’s thought process. Obviously when I’m speaking in the voice of the character himself, I am able to reveal more than I would under other circumstances. And I felt I wanted to celebrate a generation of gay men who’ve survived the terrible holocaust, not to mention a childhood, that was more than likely driven by homophobia. I thought it was time that I sang the praises of my own generation and the way in which we’ve made it this far and kept our hearts intact. I was astonished at the age of fifty to discover that I had fallen in love again, so that was a natural source of inspiration for me.

Z: Do you find that because the books are so intimate and everyone sort of feels that they can be a part of that world that it brings a bit of vulnerability to the writer in sharing that world?

A: There certainly is a level of vulnerability that comes from sharing portions of my interior life. Michael is not completely me but he is partially me and I set myself up to be judged when I set Michael up to be judged. In fact I make it even worse for myself because people don’t know what aspects of my life belong to him and what aspects belong to me. But I seem to be constantly drawn back to that process of drawing the line between truth and fiction. It amuses me to think that people might think that these stories are reality based.

Z: How has that been for your husband Christopher?

A: He runs a website for gay men over forty, but is only thirty-five himself, but for most of his life he’s been attracted to older gay men and very much like Ben in the novel. That scene where Michael finally accosts him on the street because he recognizes him from the website was very much from my own life. The only difference being that Chris was actually running the website. He has a real bee in his bonnet about celebrating older gay men and that’s part of the theme in Michael Tolliver Lives so the whole thing dovetails really nicely.

Z: What’s it like to do a big literary tour like this?

A: It depends on the schedule. My British schedule was extremely exhausting because there was a different train every day and I would often work from dawn to night. The personal appearance aspect of this experience is really energizing. I love to talk to people, I love to meet them, I love to hear their stories and I feel somehow validated after this happens. You know when you are a storyteller, part of your job is done in total solitude, namely the writing part, so it doesn’t feel complete to me until I’ve effectively looked into the faces of the people who have been affected by what I’ve written.

Z: I think it’s interesting that from a reader’s point of view, reading is usually done in solitude too!

A: That’s precisely right. That’s why it becomes such an intimate thing. It’s a message written in solitude and read in solitude and hence the bond between the writer and the reader can be very, very intimate.

Z: I generally try to read your books in solitude because I tend to laugh out loud on the train and people think I’m crazy!

A: That’s the happy side of it. I’ve had people tell me they’ve made a fool of themselves because they’ve been sobbing on an airplane. But you know there’s no better compliment to a writer, to know that I’ve shared that moment with someone who I’ll probably never meet is the thrilling thing.

Z: What’s it like to have your books turned into miniseries?

A: It’s a great deal of fun because it’s a collaborative medium and that provides marvelous company and lends a three dimensional nature to the story when everyone’s power comes to bear. By the same token, that committee nature of film making can be extremely frustrating because you don’t have the control that you have as a novelist working alone. I’ve been very lucky I should add. I think especially the first mini series established the story in the minds of a lot of people around the world, it was brilliantly executed and perfectly cast.

Z: I read somewhere an author said that making a book into a film was a bit like giving your children to your neighbours to bring up!

A: [laughs] That’s a good description. John le Carre, the spy novelist, said the process of turning a novel into a film was very much like turning an ox into a bullion cube. That is very much the nature of the beast, as an entirely different art form and you have to completely rethink it when it comes time to tell the story on film.

Z: Is there anything else you wanted to add about Michael Tolliver or coming to Australia.

A: Just the fact that I’m really excited about coming to Perth. I haven’t been here since ’82. I ran to Perth on a sort of romantic folly that didn’t work out at all. It fizzled out after two days! But I do have a really wonderful memory of the prettiest beaches I have ever seen.

Z: Wow! I wonder if your romantic folly is still in Perth?

A: I don’t know but that’s why I am being vague about it.

Z: [laughs] There’s a story!

A: Some of those Australian blokes can really woo you with their letter writing, but they don’t mean a damn thing about it! But there are a lot of guys and gals that do that. He might as well just be a rogue from anywhere.

Z: So you’re coming to the scene of heartbreak?

A: Well it’s easy for me to talk about when I am in the happiest time of my entire life. Some people are bugged by Michael Tolliver because he was so happy but I felt he deserved to be feeling the same as I was feeling these days.

The good news about getting older is that your judgement is so much better and you learn to say no to the things that really bother you but you still have the capacity for love and full bore passion and I’ll hang on to both of those things as long as possible but then who doesn’t.

Z: I wonder to what extent that fear has an impact on intimacy in our community?

A: I think that every single one of us, every little gay boy and every little lesbian growing up, we learn to create our own homophobia. We’re our own worst critics for many, many years until we get that sorted out and that doesn’t leave us no matter how old we get. There’s a constant fight in reminding ourselves that we are worthy of love and capable of giving love.

I think it’s actually a little bit harder for young gay people today precisely because homosexuality is so openly discussed, debated and condemned by fundamentalist churches. whereas in my day, I could pretty much avoid the subject, it’s now right out there the table these days and I think that makes it hard in some ways on young people coming out. At the same time the internet is there, they can find their way to other gay people and they don’t have to feel as alone as they once did.